The Fizz #82: Terry Theise finds remarkable beauty in authentic wines

Wine writer, importer, and lover of great wines, Terry Theise speaks about what makes a wine authentic, what future importers should know, and where American winemakers can flip the script.

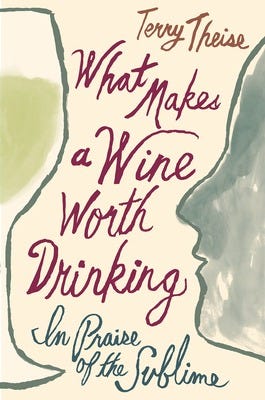

This is a little bit of a celebrity moment for me. As a voracious reader, I’m of course a big fan of Terry Theise’s wine writing, especially his book What Makes A Wine Worth Drinking. Terry has the unique ability to see beyond what’s in the glass and showcase how it moves us, changes us, and makes us respond. His books and writing have made an impact on many wine lovers, and What Makes A Wine Worth Drinking is the book I most consistency gift to others, passing that impact along to fellow drinkers.

In this issue, Terry and I speak about his upbringing, his time in Germany, and how it propelled him to a career of wine writing, importing, and making a name for some of your favorite bottles of German wines and grower champagnes. We speak to importing today, and what those starting out should keep in mind. We also delve into the state of American wine, and how makers and proselytizers can bring drinkers along for the ride.

Margot: I would love to understand a bit about your upbringing—was wine was a part of your life in your early days?

Terry: Not to my knowledge. I don't remember wine ever being on the family table. It doesn't mean it wasn't. It just means that it was not an occurrence that I paid any particular attention to. I wasn't offered wine. I don't know what my parents drank. Maybe they drank beer. Maybe they drank cocktails. Maybe they didn't drink at all. I don't even remember them drinking wine in restaurants, but I'm sure they did. Perhaps I was simply a clueless child.

I didn't grow up with wine. And in fact I didn't think all that much about it until rock and roll and blues led me to it. We drank wine casually, we being girlfriends, wife and I in our early 20s. We were living in Germany, in Munich, and so we were drinking wine over the weekend. We would drink a bottle of wine on Friday and Saturday night and Sunday too if we were feeling especially sybaritic. Most of what we were drinking was just plonk from the supermarket, and that was the extent of the relationship I wanted to have with wine.

In those days, I wanted to be a rock star and play in bands. I was a lead guitar player and lead singer. That didn't work out for me because it turned out it wasn't any fun playing in bands. It was fun playing music, but it wasn't fun looking for a rehearsal space, toting around heavy equipment and trying to get gigs, and then if you got a gig, you got it in some little shithole that was hot and sweaty and smelled like cigarette smoke, and they paid you thirteen dollars for the whole quartet to share and maybe if you were lucky, they'd give you a cheeseburger.

Margot: It’s still the same nowadays, really.

Terry: Yeah, I think you're right. So I decided I wanted to be kind of rockstar adjacent. I wanted to be a disc jockey on FM radio. I wanted to write reviews of rock records and gigs, which I did a little bit, or I wanted to own a record store or at least be a high muckety muck working in one. Then I wrote a series of columns for a British magazine called Guitar, but it was very clear by my mid twenties that this was not going to work. I didn't know what I would do with my life. I had the occasional dark thought that I was simply a misfit who really didn't have a way forward.

And then—and this is the story most of us wine people have—by happenstance, I saw a bottle of something in the supermarket called Riesling. It was a 1971 Kabinett from the big giant Mosul co-op, and I had vaguely heard of Riesling. I thought, well, it didn't cost more than the plonk that I was already drinking. So I brought it home. And when I drank it, I had the moment. This was not an experience necessarily of exposure to great beauty, but it was just an amazingly interesting flavor. I was really taken aback.

I had the “what the fuck?” reaction. How does anything taste like this? After that, I decided I should probably set about exploring because I don't want to accidentally have this experience randomly. I'd like to learn whatever it is that I need to learn to bring these wines into my life more purposefully. From that little seed, mighty forests grew.

Margot: That’s wonderful. Do you see alignment between wine and music?

Terry: Yeah, I think they are fraternal twins. The thing that unites them is each of them has a an overtone of science. There are certain things one needs to understand if you're going to understand wine cognitively and certainly things you need to understand in order to understand music theory and such. There's a connection between music and mathematics as well. But the thing that I think is the most numinous connection between the two is the inexplicable nature of both of them. Music is beauty without narrative. I mean, you can have an implied narrative such as in opera, or you can have sort of an intended symbolic narrative or metaphorical narrative such as in film music, which is designed to make you feel certain ways.

But the ultimate mystery of music is, even when you understand theory, even if you understand the mechanics by which emotions are engendered in the listener, you know what harmonies to use to create which feelings, you still don't know how it happens. There's no explanation for how an arrangement of tones can make us feel so deeply and so mysteriously.

Leading us to wine—we don't drink wine because we're thirsty. It's not like eating food because we're hungry. We drink wine sheerly for the experience of the pleasure of its taste. In some cases, of course, that pleasure ratchets up to experiences of remarkable beauty. Wine is only really important insofar as it's a kind of a glide path into the world of beauty. It won't quench your thirst. It is simply there to delight you. Like Ben Franklin said, it's proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy. That's where wine and music seem to me to overlap, because they are a delivery device of pure beauty. The meaning in which is implied mysteriously. And to appreciate both, the way you and I do, involves a certain comfort level with the mystical.

Margot: I love that. In What Makes A Wine Worth Drinking, you speak to the authentic wine, your passion for an authentic wine. What does that mean? What makes a wine authentic or inauthentic?

Terry: Because I was living in Europe when I got into wine, I basically set about to go exploring. And what I had been told was that the salient fact of wine was where it came from. So in effect, the message was that terroir was the first principle behind which all the other principles stood in line. So I went looking for the great vineyards. In those days, and still to an extent in these days, the German production culture was just tons and tons and tons of little family wineries. What imprinted upon me was that was what wine was, it was something that was made by little families intimately connected to their land working artisanally. Now “artisan” is a buzzword basically, but this was the reality of wine for me.

Later when I realized that wine could be an industrial product, there was no connection there. I thought well, what's the point of having disconnected wines? So that led eventually to the notion that the disconnected wines, wines that were formed as products to appeal to a market that had been studied and the marketing people knew how to manipulate that consumer, that that was inauthentic.

It was just another product, like I say, it was like a box of Triscuits. And box of Triscuits have their use, and every once in a while, if you are in an airport, at a Regency, in some little town in Montana, and you see Dry Creek Chenin Blanc on the wine list, you think, okay, well that's reliable. Not to cast any shade on Dry Creek, who are among the better, but you know what I mean. The principle being give the devil his due. The skills involved in producing what I call inauthentic wine are still skills, and they have their place.

But it's a short life. You know, it's a little life and our adult life, our wine drinking life—what is it going to be? I mean, how many decades is it going to be? Do we really have the time to waste on these “wine as product”, as opposed to wine as expression? What's authentic in wine is first and foremost that connectedness, and the question of how good the wine is comes later. You can have a very ordinary, let's say, Silvaner that's grown in unexceptional soil by a vintner who isn't especially talented. The question of how that guy stays in business is for another day. And that isn't a wine that's worth drinking, but it is an authentic wine.

Yeah, the industrially made wine might taste better, and that leads people to the confusing notion that you should drink what you like. Doesn't matter how it was made or who made it, but that's a false choice. You enter the world of the authentic wine. It doesn't mean there's a guarantee that everything is going to be rapturously good.

Margot: How does this connect to natural wine? Since natural wine is mostly made by small producers, does that lead to all natural wine is authentic?

Terry: Well, the movement is healthy, generally speaking. The emotions and philosophies that led into it are understandable and generally speaking, wholesome. The problem, of course, is the lack of discrimination probably by some of the producers and certainly by many of the consumers of that genre of wine whereby they do this kind of Orwellian doublespeak and wish to persuade us that flaws are actually virtues. I mean, if you're really going to swallow that Kool Aid, then it sounds to me like you took your wine classes from Kellyanne Conway.

Margot: You mentioned wineries doing a lot of marketing—in the European small winery scene, there's not a lot marketing, but here in the United States it's different where we do see a lot of small wineries lean into marketing as their main way of getting their word out. Except for some regions, we don't really have the oomph of AOCs behind us, even though we have AVAs here, but consumers don’t really pay attention to all that in America. For American wineries, does marketing play into how you see authenticity in a wine?

Terry: Generally speaking, it's probably different for the New World overall. You know, it's changing in Europe—the street that had fifteen little wineries on it now has two or three larger wineries that are larger because the little guys folded in their tents and someone had to buy their vineyards. Otherwise they would go fallow. So when I started off doing this, when I would knock on a grower's door, they didn't have tasting rooms. They didn't have tchotchkes or, you know, caps or buckets or monogrammed corkscrews or any of that. You sat in their living room or whatever little spot in the house they had to receive the drop in visitors.

And to a large extent, that's still true. Recently, this is parenthetical, but recently the EU has had a budget for producers who have wanted to create sort of visitor centers. And many of them have. And if next time you go on a Europe trip, you'll probably visit a lot of those places and you'll go, man, this cost a bunch of money. But you know, there's still plenty of wine growers who will invite you into their kitchen and it's very homey and very sweet and very dear.

Look, there's industrial wine in the old world as well. Plenty of it. And it's just as unseemly as industrial wine is any place else in order to create a large enough market to absorb all the product that you produce. You have to do marketing. There's no way around it. The marketing organizations that different countries have that do generic marketing, some do a certain modicum of good, some do more good than others, some do no good at all. It depends on their budgets, and it depends on how smart the people are who are running those marketing organizations.

The grower, unless they are large enough, and incidentally profitable enough, don’t have a PR and marketing budget, and really can't do very much of it. You know, generality is only ever generally true and there's thousands of exceptions, but the startup wineries in the new world, I think understood marketing costs as a necessity of doing business.

The “cool” places to go in the U. S. are the places that are still relatively unknown. Upper Peninsula of Michigan, for example, to a certain extent, still the Finger Lakes of New York, Long Island. Those are still in many cases, little artisanal connected growers who really don't have marketing costs, and they, to the extent that they get distribution in major markets, they depend on their distributors to do the marketing for them.

Margot: I'm curious to understand a little bit more about how you got into importing. You started writing music reviews. You went on to write wine reviews and newsletters. Where did that importing opportunity hit?

Terry: When I got back to the U. S. in 1983, all I knew is that I wanted a job in the wine industry. I had the naive notion that I might be able to make a living writing about wine. That notion was very quickly demolished. I realized I was going to have to sell and what tier in the industry that would entail, I wasn't sure. So I didn't know if I wanted to work retail or wholesale. I had the strange idea that wholesale was somehow a superior tier to retail.

I was hired by a distributor in Washington, DC. I was hired reluctantly by that distributor persuaded by a wine supplier who was important to them and who took me seriously. And that was Robert Katcher, who I owe a great debt to. They threw me into a territory that consisted either of the accounts that had never been called on or the ones that they had been thrown out of. So in effect, I was kind of thrown to the wolves. But in my Munich days, one of the things that I did for a living was I worked around the US Army as what they call a civilian component. It was a Department of Defense job, but it wasn’t active duty military. It exposed me to a very wide number of people, and different types of people. I enjoyed that multiplicity of different types of people, most of them not like me at all.

So, when I was thrown into this territory, I realized I actually had in my toolkit the ability to get along with all kinds of strange people. I actually did business. I mean, I wasn't any kind of a salesperson. I had no expertise in sales, you know, I didn't go through the Gallo Hitler youth programs, but I managed to do it because I suppose I didn't know I couldn't do it. That's how I made a living, but I wanted to be in the fine wine end of the business, and eventually I managed to headbutt my way into that.

Among the wines that we were selling were German wines. We were buying them from a supplier and it suddenly occurred to me—I have 25 really good close friends over there in Germany, wine growers whom I know whose wines are not represented in the United States. So I thought, well, that would be something fun for me to do, but how do I spin it to the owner of the company? My pitch was, we're selling X amount of German wine right now at Y profit. What if I told you that I could quadruple that and double the profit? He kind of laughed at me and said, you know, what would it entail? And I said, well, a modest upfront investment. Send me to Germany for a week or so and let me put a portfolio together, and then we bring those wines in directly. We have an import license. We can do them directly. We take the importer's margin and the distributor's margin, collapse the two margins. So if you've got like one entity making 25 points, the other making 25 points. You don't make 50 points. You make 35 points, and you look cheap, but you're making big money. I sold it that way as a pragmatic matter. That was how I was off and running!

Margot: What were some of the challenges that you encountered in those first couple of years?

Terry: Indifference on the part of the customer. Those were not bad days necessarily for German wine, but I made my first offering in 1985. The market had been flooded with German wines from what was considered to be the great vintage of 1983, which was very large in size and which also corresponded to a spike upward in the value of the dollar against the Deutsche Mark.

There was a tremendous amount of wine and it was really cheap. When I showed up in 1985, the dollar had tanked by then, the crop size was small, the prices were higher, and the market was saturated still with all the wines that they had from the ‘83 vintage. I did what I could. I had customers, I had friends, I had fellow German wine freaks. It wasn't so bad. But I started realizing after a couple of years, this was going to be a pretty heavy rock to push up a pretty steep hill. I was still working for the distributor. So in effect, I had a day job and a salary. What it means to put not too fine a point on it was that I could afford to fail.

Margot: Interesting. I'm curious what some of your big aha moments were as you were importing first German wines and then champagnes? I know several people who are interested in starting their own importing businesses now from the Czech Republic or Croatia or Georgia and I wonder what kind of wisdom you would pass on to these folks as they start their ventures.

Terry: Fundamentally, the wisdom is before you sell the wine, you're making a kind of meta-sale. You have to sell to the potential customer the certitude that this was a type of wine that they really should have. Once you persuade them of that, then you can set about the business of selling them the actual individual wines that you have in your portfolio. So your initial purpose has to be to justify your existence, and then you let the wine sell itself. Assuming that the wine is good. You justify your existence by attempting to persuade people that your passion is contagious and justified, and that's the long and short of it. That's what you must do.

Obviously, you have to have a decent enough palate to choose good wine and you have to have a savvy enough sense of the market to feel that there is a sales potential, provided that the wines of course are good. But the thing you really have to have is that almost—messianic is too strong a word, but you could almost call it a religious passion that you know that you are doing the work of the angels, and if you give me five minutes, I will convince you of that. That was, if you will, my aha moment, where I realized the job was to sell wine, but the work was to inculcate in the customer a mindset that would convince them that this was something they ought to be doing.

As far as sales were concerned, my moment of revelation was that I didn't have to sell wine to 25 or 30 accounts in any given market. I only had to sell it to the three or four opinion leaders in those markets and then the others would follow. It was kind of like guerrilla warfare and particularly in the restaurant trade where in any given market, there are sommeliers who are the market leaders and others watch what they're doing. If the alpha sommelier has a section on her wine list that has six or seven Croatian wines on it, believe me, the other ones are going to look and go, hmm, what does she know that we don't know yet?

Margot: That's really interesting. So finding those champions and really selling into them is important.

Terry: Yeah. I mean, that's how it was done. Luckily this is a renewable passion because if I weren't just blasted into ecstatic orbit by the wines that I was selling, I could easily have become very discouraged by the relative indifference in the marketplace. I was probably pretty tiresome because I was just so bloody convinced that not only were these wines remarkable, but this type of wine was the finest example of all that is great and good about wine on this earth.

Margot: I think your tenacity is what got folks excited about Rieslings and grower champagnes. You had that consistency and a vision for what was interesting and authentic in these places and your vision around where these wines would go. Where is that opportunity for of our local American winemakers?

Terry: Well, I must say that I align myself with John Bonné in this, that I think that the community of people who are making the kind of rebellious style of California wines, who have moved away from the big and overblown sort of bombastic, are the ones to me who are doing the most fascinating work. A classic example of which might be Forlorn Hope. Those are the kinds of people whom I will always follow. They're the iconoclasts, the ones who swim against the tide.

If somebody asks me, as I occasionally have been asked, how do I find the best values in wine? I say, oh, that's easy. You think an essay is going to be required to answer that question, but I will answer that question in four little words. Bet against the crowd. It is those types of producers, whether they're in California or elsewhere, who are making the kinds of wines that are betting against the popular kids. That community is ever burgeoning, it's ever growing, and you know, they're learning by doing, there's a lot of trial and error involved, but oh, their work is worth supporting, enormously worth supporting.

Margot: What does that support look like? I consistently hear from winemaker friends that folks aren't drinking American wine, or we need to raise our prices because glass is more expensive, or what have you. How do we stand up as champions for American wine the way that you have stood up as champion to grower champagne and to German wines?

Terry: Well, you have to rewrite the script—the cliché about American wines was justified, certainly enormously so in the last 25 years, 30 years, in the Parker era, let's call it and which is still to a certain extent justified, is that the wines are fatiguing, that they're just huge. That's a script I think needs to be rewritten. We need to remind people that this isn't venture capitalists and refugees from careers in accounting or whatever. These are hippies that are just trying to make the kind of wine that they want to drink.

The thing that's difficult, Margot—the advantage the old world has is that they've already amortized the startup cost. We in the new world, we have debt to service. The cost of doing that is going to add disproportionately to the cost of the wines and can make them less than fully competitive in the marketplace. I think for people who want to fly the flag for American wine, we have to first remind them, it's not all the big swinging dick collectors who are building $25,000 cellars to showcase the vertical vintages of magnums of Screaming Eagle Cabernet that they were able to buy by taking a second mortgage out on their fourth house—you know the type.

Wine is not the purview of those people. There is a very large and very healthy community of people who want nothing to do with that type, who are going to be the clientele that will rescue these kinds of wines. I have a friend who has exited the industry, sadly because he is precisely the kind of person the industry needs, because he just got jaundiced with the whole collector mentality. He just said it's not fun anymore. I can easily see how it wouldn't be fun. You should become somebody like I was. I was one of the few people who had an enviable job in the wine industry. Everything I did, I did for love and fun.

Margot: You said that many think that American wines are fatiguing. I had a dinner a couple weeks ago and one person said he doesn't drink American wines because they're all these too big, too sweet too something. We’re learning to position American wine to consumers as something that is worthy of being explored, something that is multidimensional and that covers a lot of ground. We're not talking about a single plot of 20 acres. We're talking about a giant country with a ton of different kinds of styles and varieties. These are mostly small winemakers who make the wines that they want to drink.

Terry: It's even talking about American wine in a way a little bit too nebulous, probably you wouldn't talk about “American food”. It's like which American food, right? The conventional wisdom always tends to be about five years behind what's actually happening. If somebody says that to you, the American wines are huge and sweet and fatiguing and overall, blah, blah, blah, yeah, that was true, and to a very small extent still is. But there's a recoil from that. Pay attention to what's going on now, a recoil from that whereby the wines are becoming less gigantic and less laden with this kind of gooey sweet fruit and, and less massively alcoholic. It might be time to take another look.

Margot: Absolutely. One thing I admire about your writing is that it has been so sure-footed. I've read a lot of your wine reviews over the years and obviously your books, and you convey your opinions and beliefs in such a solid way. How do you trust yourself in such a sure way?

Terry: I'm not sure what the alternative would be. If any writer didn't trust herself or himself why would you then begin to write at all? You have to start from the notion that you have something worth saying and then you cast your bread upon the water and the readership decides. It's a really interesting question, and if I answer it honestly, my answers could sound unseemly, but I do trust overall in my aesthetic judgment. That is to say, I think I'm a reasonable critic. It doesn't mean I'm always correct, and it doesn't mean that my opinions are unassailable, but the things that enter into my sphere of judgment, whether it's books or music or wine or food, I feel like, okay, I bring a reasonable sensibility and a reasonable intellect to the party.

I'm the last person in the world to ask about paintings or sculpture or photography or anything. No one should take any opinion seriously that I might espouse. And in fact, hopefully I'm smart enough not to espouse opinions about those things because they are worthless. But when it comes to wine, I don't know that I have a great palate. I think I have an adequate palate, adequate to the task at hand. I have good power of concentration. I have good memory. I have the kind of mind that is skilled at cataloging things. So it forms relationships between types. That makes it fairly easy for me to be able to put wine into conceptual compartments, which is honestly a shortcut in many cases for being able to assess this whole thing.

I think like any writer, if I look back far enough, I kind of cringe at some of the stuff that I let myself write. I was talking to Karen McNeil about this, and she says it's a mistake we wine writers make. We tend to think that the last thing we produce is the best thing we ever produce, and it's not always true. She's right, of course. I do think that if I follow the arc of my writing over 20, 25 years, some of that shit was good back then. Over the years, I think my writing's gotten tighter, more pithy, less flowery, a little more pointed, maybe a little more sober. But that's also just a function of age.

The thing that made my second book worth writing and seeking to publish was that it was not only a step forward from reading between the lines, it was a different kind of book and it was a larger question about the interface of beauty and mortality, and how does that pertain to wine? In the years that I was writing Reading Between the Wines, I was too young to have those kinds of thoughts. Turning 60, which now I feel I look back on it and kind of laugh, you know, I thought, well, I turned 60 and I started thinking about mortality.

I'm seventy-fucking-one now, mortality is front and center. I'm looking back at that and thinking, oh man, you youngster, you had no idea what was in store for you, but it was a wake up call. So I realized that I had a different relationship to wine than I had had as a younger person. I thought, what does that mean? Does it mean anything? If it does mean something, is it a meaning that's worth discussing with other people? Am I the person to do it? Most of my writing is improvisational. I don't necessarily have a theme that I've set up in advance.

I may have an idea or a notion, and I think okay, let's begin with that. I'll write a sentence or two and that leads into the next part and that leads into the part after that. A lot of times by the time I get to the end of any discrete piece of writing, I'm in a different place than I set out from. Sometimes an entirely different place. In that sense, my writing is kind of essayistic.

How does any of us do it? We go out into the world feeling like we have something the world can use. I think it has to be that. Otherwise, we crawl into a hole and bury ourselves. The membrane between that sort of fundamental confidence and conceit or pride is a very thin membrane. Occasionally I am asked, are you proud to have created the grower champagne revolution? I always say, oh, I don't like that proud word. Pride is something I need to keep a certain distance from. It's a very seductive temptation. Sure, I'd like to be proud of having done that, but I would rather not be proud at all. I'm glad to have done the work. I'm just glad it was useful.

Margot: I think that humility and authenticity really comes across in your writing.

Terry: Thank you. I try to avoid the humble brag. I find that if I am too serious for too long, I feel like I need to intrude with something goofy or obscene because it starts to feel precious. I know what my flaws were as a wine merchant and as a writer, I'm trying to outrun them. I'm running as fast as I can and they are a step or two behind me constantly.

Margot: How often do you drink wine? Is it an every night thing? Is it a once a week thing?

Terry: Every day.

Margot: What happens when you run into that wine that is worth writing about? How do you know that you are moved by a wine?

Terry: I think the answer to the question is the question, you are moved because you are moved. The basic architecture of my website right now is that I have erstwhile producers sending me samples, and I'm writing about those to keep current with their wines and to let readers know the kind of work that they're doing. In effect, continuing the work that I did in my catalogs. I used to write tasting notes much more frequently than I do now. If you went back three to five years, there would probably have been 15 or 20 times per year that I would take out the notebook and write a note about the wine I was tasting because it was so interesting or so beautiful and I just wanted to record it. I wanted first not to forget it and second to see if by writing about it, it would lead me into something that I didn't realize I wanted to know.

That doesn't happen very often anymore. I think that too is a function of getting older. At this point, I probably will pause while drinking a wine to write about it maybe three times a year, and then it has to be something that very quickly removes me from itself. There's a point where you're kind of blown away by how beautiful the wine is. That for me is the entry to the process, not the exit. Suddenly the entry to the process is you're not thinking about the wine anymore. Now you're thinking about beauty, and poetry, and mortality, and love, and friendship, kindness, and the mysteries of birdsong. You could be thinking about any or all of these things, and you've got the wine in your glass, and all you can do at that point is just say, wow, hello, friend. I didn't know where we were going to go, but I'm glad you took me.

Sometimes in that moment, you don't want to freeze the moment by writing about it. You just kind of ride the wave. There are times when I really want to try to do both. You know, there's like, oh my God, this is an insight. I'm really afraid I will forget this if I don't write about it, and it's like when you have a really funny dream, and you wake up from it in the middle of the night, and you say, oh, I'm going to tell my partner about this dream in the morning, because this is really hysterical. And the next morning, you don't remember it.

Margot: It's interesting to hear about the entry and exit and how that's changed for you and moved further down for you. Because you've had so many amazing wines throughout the years that now your goalposts have moved a little bit?

Terry: You could say I haven't had very many big deal famous great wines in the world. Being a merchant selling German and Austrian wine made those wines unaffordable for me. I didn't have the kinds of friends who collected those kinds of wines. I had a friend who brought over a bottle of La Tache 1982 in the last few months. That was the first time I'd ever had a bottle of La Tache. I've had more than my fair share of grand German wines, thankfully. I've had beautiful old champagnes from the vanishingly small number of growers who kept them, or whose fathers kept them. That’s always incredibly special.

Margot: Terry, thank you so much for your time. The way you speak about wine is infinitely inspirational.

If you’re looking for magical wine writing, be sure to get copies of Terry’s What Makes A Wine Worth Drinking, one of my all time favorites, and his earlier Reading Between The Wines. Keep in touch with his work through his blog.

So cool, and very enjoyable to read. I picked up a copy of What Makes A Wine Worth Drinking on your suggestion and really connected with how Terry thinks about wine. Relish the celebrity moment and keep up the great work!

Thank you, Margot, for turning the spotlight on a true hero in the sometimes thankless work of bringing American audiences closer to German wines. Terry is in a league of his own. His writing deserves the widest possible audience, especially, I think, among younger readers and would-be lovers of great wines.