The Fizz #83: Sean Turley is building an apple identification task force, and it starts with you

Apple expert Sean Turley and I discuss why apple identification is important, the history of apples in America, and his new book Practical Pomology.

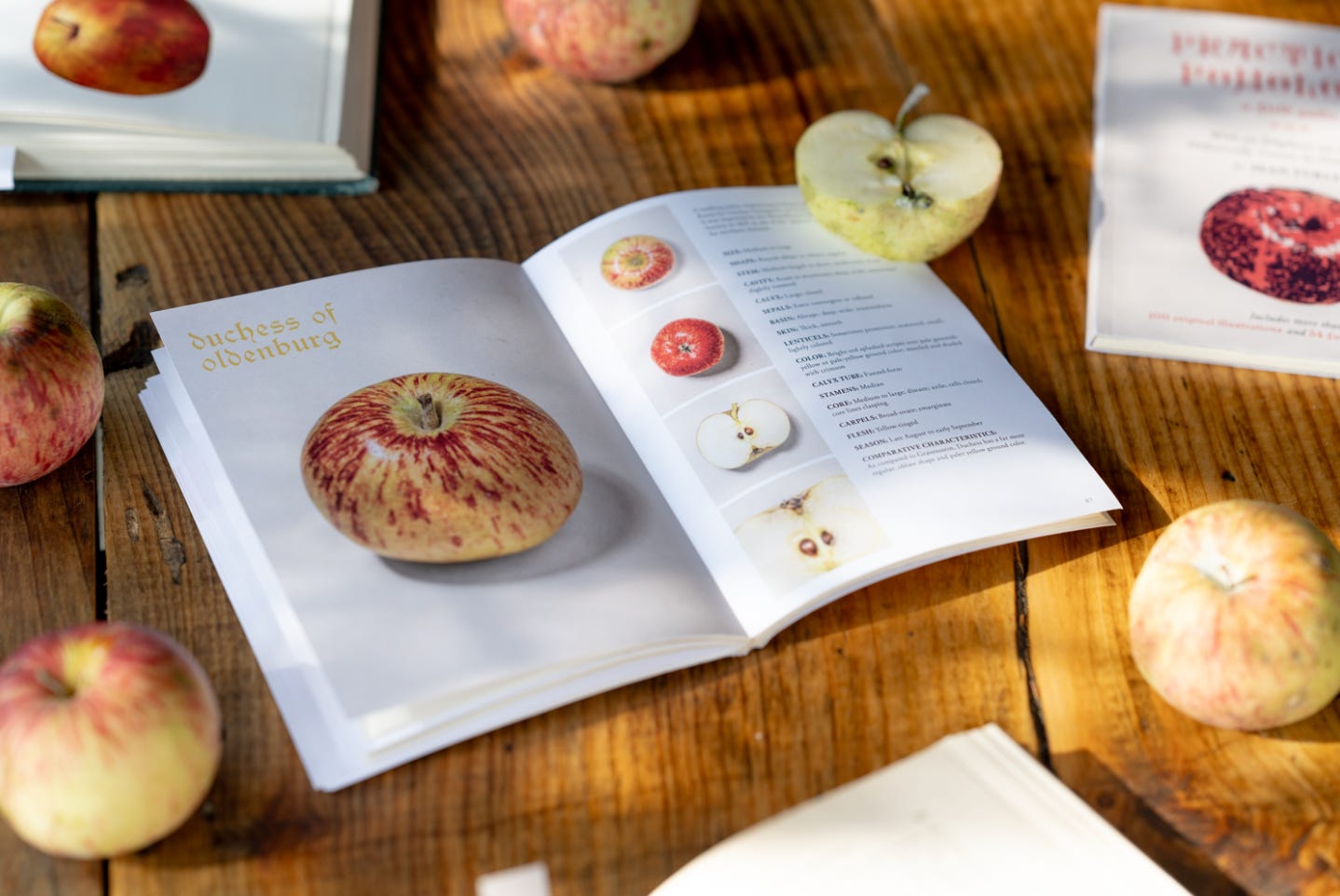

For this issue of The Fizz, I sat down with Sean Turley to talk about apples. OG Fizz readers may remember that Sean was featured on The Fizz in 2021 speaking about their Maine Cider Club, and the work they’ve done in the apple community in New England. (An aside: Sean’s Instagram is a veritable apple database). Three years later, they’re publishing a book I’m very excited to tell you about. Practical Pomology is a field guide for the apple-curious, whether you’re a seasoned forager and cidermaker or someone who just loves that big apple tree in your neighbor’s yard. It’ll teach you how to recognize the difference between seedling and grafted trees, identify the apples you come across, and ultimately understand their traits. What you do with that long lost fruit is up to you.

In this issue, Sean and I speak about the importance of keeping these lost varieties alive, how apples went from diverse and omnipresent to the five varieties you see at your local market, and how their new book came together.

Margot: Can you tell me why is the identification of apples important? Why should we care about the different kinds of russets or the variety of tree in the backyard of our neighbor's house?

Sean: So, the fundamental fact about apples that you have to start from is that every apple seed produces a unique fruit. Unlike other fruits, apples do not grow true to seed. So as a result, if you have a variety that's out there in the world, say MacIntosh is a good example, that's a clone of an original MacIntosh tree from probably the late 1700s in Quebec. It's genetically identical to all those other MacIntosh trees.

Identification has tremendous importance. For one, you'll be able to tell whether an apple is identifiable. Because there's that possibility that a seedling is what you're looking at and it's unique, that might inform decisions about how you might try to use it or what it is, or where it fits into your orchard. If it's something that's completely unique, whether or not to use it and propagate it is an open question.

The biggest reason is because we've been at somewhat of an information deficit on apples. We have all these old sources mostly mid 1800s to early 1900s that identify all these apples that used to be fairly common in the United States. As of, let's say 1900, the count was probably about 10,000 different apple varieties in the country—some of them very local and regional, some of them nationwide. When people wrote about this and talked about these apples, they were mostly academics who spoke in kind of a code. I mean, they had their own pomological language that they used. In some cases, that's all we have remaining of descriptions of these apple varieties, is the coded physical descriptions of the fruit, or the kinds of russeting, as you mentioned, or lenticels, what their shapes are.

So there's been an inability to access that information and use it to try to find lost varieties. The reason it's good to find lost varieties is for one, as our climate changes that lost fruit might be really adaptable to what we're currently facing. Apples that we've lost in time could serve a pretty important purpose. They're important historically in terms of regional agriculture and sociology of what apples people are using. Then, obviously, it's also interesting in terms of cider fruit and what people were making beverages out of historically.

The book is a bit of an attempt to provide a kind of decoder for these old sources. It allow you to make the distinction of am I even looking at a grafted tree, meaning a clone that has a name? If so, what is it? That might help you access how it might be used or how it was used historically.

The knowledge to do this work, especially in the modern era, is probably possessed by less than a dozen people in the world—less than a dozen people know how to do what the book shows you how to do. Just because all these older sources use technical language, and these academic authors didn't define what that language meant. Although there might be some illustrations, they didn't comprehensively illustrate everything so that a novice could read their book and be like, oh, okay, I can identify MacIntosh. They just assume they're writing for an audience that knew what a MacIntosh was, and there was no reason to do that. There was no thought that, oh, lay people would use this information as an orchardist, a cider maker, etc. It just didn't exist.

The people who do it currently, like John Bunker, had to basically learn it himself and figure out by problem solving what all these words meant. Without this book, it's hard to do that work, if not impossible.

Margot: I love that you’re really focusing the book on providing access to this skill. That’s really meaningful. You mentioned we had 10,000 different varieties of apples at one point in the United States. How come when I go to my local co-op I see four types of apples, and they're the same apples that I would see whether I lived here in Maine or in Texas or in California?

Sean: So generally speaking the history of apples before 1900 were these very localized agricultural systems. You had a lot of subsistence farmers. You had some larger scale orcharding, but basically when people came here from Europe, they brought seeds, they planted the seeds, and so different parts of our country developed different apples. Then, ones that seemed really adaptable or great for various purposes would spread beyond that region. That was economical. Even in a state like Maine, we had a really vibrant and profitable apple industry for many decades where we would ship apples to Europe in barrels, we’d ship apples throughout the country, but what happened as of like 1890 / 1900 is the railroad became more cost efficient.

Growing apples in Washington State, which is perfect for apple growing—it's slightly desert-like, lots of sun and not a ton of water—apples trees don't like a lot of water. Basically because of the advent of the Intercontinental Railroad, it started to be cheaper just to grow apples in Washington and ship them east. It became even cheaper to do that as compared to getting apples from Maine to Massachusetts. Because of that, there was this huge consolidation of apples. We became more of an urban culture, and so people moved off of those farms where they had an orchard of maybe ten trees and started just buying apples.

Cheap apples from the west also meant that the apples that were preferred were ones that stored well and looked good on a shelf—Red Delicious being a great example of that type of apple. It had to survive a fairly long journey across the country before refrigeration existed. Then it had to sit on the shelf for like a month. So what was ten thousand became ten that were grown at scale. Some local regional orcharding survived, but it was it wasn't very profitable.

The other thing was that people's priorities changed, the types of apples they wanted changed. Apples were a crop that people used year round because you could store them well and make vinegar, cider, and alcohol with them. Now that people weren't living on these farms as much, the need for the more interesting apples kind of disappeared.

Margot: It's interesting to hear that the interest in apples had faded and the way that people used apples changed. But now, and especially after the pandemic, there's been so much more interest in homesteading, especially with Gen Z. Have you experienced a rise of interest in orcharding or foraging for fruit?

Sean: Absolutely, there's been a big spike in people very interested in foraging and growing. So either going to these old farmsteads and homesteads and finding apples and taking them, or going out and locating unique apples that maybe show some promise, particularly for most people who forage for cider making. That's because all those commercial apples don't actually provide any of the chemical structure you need and polyphenol content you need for tannin. They're relatively useless. I mean, unless you make cider with guava MacIntosh sea salt and lavender—I'm sure that actually exists which is kind of disturbing. Cider has driven the interest and as you said, there's been more localized agriculture and reconnecting with some of these older varieties that would have been very common in the past.

Margot: How does someone interested in cidermaking use this book?

Sean: It’s useful as a way to describe and communicate about the apples you do find. So every year, for example, there's a pomological exhibition in Massachusetts that takes place around by Gnarly Pippins, or Matt Kaminsky. Part of the work he does every year is goes through and describes all the apples at the exhibition, because the idea would be that if they end up being propagated—people end up collecting scion wood and grafting them into some other property—we’d have a common understanding of what the apple looks like and what to use it for.

It's a tool for tracking, identifying, and describing new apples that might down the road be the apples cidermakers use. It's also helpful in terms of that initial analysis of: am I looking at a seedling tree, so this is unique, or am I looking at a grafted tree, in which case it's not unique and I try to figure out what it is. People who are particularly looking for new fruit, it's actually good to know if you're encountering a grafted tree or not.

Margot: That’s awesome. How long have you been in this apple game? It's been over a decade, right?

Sean: Yeah, a decade-ish plus. A while.

Margot: What have apples taught you about American history and culture and what are you learning about the apple culture as it moves forward?

Sean: Yeah, so one of the most interesting things to me is—it's kind of mind boggling. I have found it mind boggling to think that both in terms of persistence, as I said, MacIntosh originated in probably the mid 1700s in Quebec, and we still have it. There's thousands upon, maybe millions of MacIntosh trees. It's just fascinating that we could be still growing and using the same fruit that has been around for at least 250 years.

It's also really interesting to me that despite America being a collection of communities, for the most part, with no speedy way to travel from one region to the next, despite that, apples that were renowned for some reason did actually spread. MacIntosh went from Quebec to Massachusetts to all of New England to out west. So it tells you a lot about people's connection to agriculture, their willingness to try to move things and grow things that are useful. It's fascinating to see how things have jumped regions despite localities.

Local apples like Newtown Pippin, an apple that originated in New York, gained a lot of renown because Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin really loved it. That apple now is very widely grown, not in New England or New York anymore, but in Virginia and California. It got to California in the 1800s and really took off. This piece of scion wood went across our entire country at some point, in which that would have been pretty difficult to do, just to grow a different type of apple.

Looking forward, as you noted, the like five supermarket varieties, I think people are becoming more aware of the possibilities of apples being more diverse than people think. It's also really interesting to me that a lot of the “new” apples we have in the world are because of breeding programs, and it excites me that we might be going back in time a little bit and finding things in the wild that are useful, particularly for cider making.

Engaging in an old practice of assessing seedlings as a means for American cider making, to create our own cider apples—that’s big. Cider apples to the degree that people are planting and using them are varieties from England or from France, and that strikes me as very silly. Silly's not the right word, I guess. Kind of a dead end. A lot of these apple varieties grow well in England, but not here. Why are we making cider with English cider fruit? Why don't we make cider with American cider fruit? Well, most of our historical fruit's not good for cider, so why don't we go out and find some cool new apples?

Margot: Absolutely. You mentioned John Bunker earlier. I’m obviously a superfan. You have a really close relationship with one of the most accomplished apple experts in the country. I'm curious how you and John worked together in the development of this book, and what have you learned from him in that time?

Sean: Oh, a tremendous amount. So John, this book could not exist without him. He actually spent thirty years decoding all those things in text in terms of what the words meant and the different parts of the apple, and all these things that are expressed in the book. It would be basically empty without his contribution to it. This book itself, we've been probably working together on for five years, six years. I floated it to him as an idea, and one of the major limitations of the book actually was finding an illustrator who could do it. We know plenty of talented people who can illustrate it, but if you don't actually know how to identify the fruit, its kind of pointless to engage in that type of illustration. Finally through a lot of pleading John agreed to do the illustrations himself, which was the breakthrough for the book.

I've learned how to identify apples from John. More globally, I don't know what I would be in this world without him, in the sense of like, what I care about, whether it be future fruit things, seedlings out there in the world, or historical stuff. His enthusiasm of keeping this torch going—I know that he's trying to hand down things to future generations and I really respect anyone who's thinking about that. It's funny because part of the book is driven by what has been John's work.

For the last twenty years, at least, John has set up a table at the Common Ground Country Fair and people have brought him apples. As best as he can, he has tried to identify them. But the funny thing there is that it’s such a bottleneck. If you just have one person who could do that and you have no resource to point people towards to learn to do it themselves, you can accomplish very little. I think what John likes about the book is that we can finally get this knowledge out there. We can both help teach it, but then also help people teach themselves. It's gonna be really important.

Margot: That’s so inspiring. I’m excited to see how people use it. How did you choose the thirty four varieties that are highlighted in this book? For folks who are outside of New England, and they want to identify an apple that's not featured here, what is their path?

Sean: Yeah, thirty four is an arbitrary cutoff. I think it was originally thirty two and then became thirty four because I realized there were a couple that I really wanted to capture. I would say at least twenty of these apples are persistent across the entire United States in various amounts. Most of the apples that spread to places like Colorado, California, Idaho Oregon, Washington State, the Midwest came originally from New England and when people traveled, they would have brought these apples with them. A good chunk of these actually appear everywhere.

I think what'll be interesting is by actually providing a way to identify those apples easily, it might help us better understand where those apples are grown. There might be these lost orchards out there where you could find these things, but you wouldn't know what they are, and you wouldn't be able to identify them. At least half of them you would expect to find everywhere, and so they should provide a foundational set of knowledge around apples that you're likely to see.

Margot: If I come across an apple somewhere that is not one of these thirty four, what do I do if I want to identify it?

Sean: Yeah, so there's two general sources. The first thing is you would use the book to describe the apple. So you'd break it down more into text. You'd look at the images, or you'd look at the illustrations, and you would actually write out a description. The way that would be helpful is then you can go to these seminal resources like S.A. Beach’s, Apples of New York. There's a bunch of late 1800s, early 1900s pomological texts where all these descriptions are written out. You could actually then look and see, okay, Joe Schmo, who owned this orchard, told me they thought it was Northern Spy. Well, let me go look at what the description of Northern Spy is. I want to look at the description of the apple that I have in front of me. Oh, those do look like the same thing. Or no, they don't. Generating a description by use of the book then allows you to actually access those other sources to figure out if you have some lost variety of some kind, and also to rule things out.

The other piece of it that ends up mattering is you can then compare what you have to the USDA watercolors. So, in the early 1900s, the USDA commissioned several thousand watercolors of fruit including five or six thousand apples. Knowing a bit more about what the apple looks like, you could use that resource to try to figure out what you have.

Margot: Can I mail my apple to someone?

Sean: [laughs] Yeah, you can try. But this is kind of the issue is I think everyone who does this work is so overwhelmed by it.

Margot: You're like, please don't mail me your apples!

Sean: Yeah, exactly. Don't mail me your apples. No, I think that's part of the main idea of the book. Instead of people mailing apples, why not mail the book to them, and they can identify it themselves! But you're right, I know, it'd be great if there was just like some mail order service. Hopefully we're going to train a citizen's army to do the work so you could just consult your local apple identifier.

Margot: I can’t wait to join the ranks. Thank you Sean and best of luck on your mission!

You can purchase Practical Pomology on Kickstarter, the platform Sean is using for pre-orders. Don’t delay though—the book is on sale until January 1st, but after that, they’re not going to be printing more copies. You’ll only be able to find it from small re-sellers (if you’re lucky). Follow Sean and their work on Instagram to stay up to date on apple news and events.